© 2011 Naturesfury.net

What is a tornado?

According to the Glossary of Meteorology (AMS 2000), a tornado is "a violently rotating column of air, pendant from a cumuliform cloud or underneath a cumuliform cloud, and often (but not always) visible as a funnel cloud." Literally, in order for a vortex to be classified as a tornado, it must be in contact with the ground and the cloud base. Weather scientists haven't found it so simple in practice, however, to classify and define tornadoes. For example, the difference is unclear between an strong mesocyclone (parent thunderstorm circulation) on the ground, and a large, weak tornado. There is also disagreement as to whether separate touchdowns of the same funnel constitute separate tornadoes. It is well-known that a tornado may not have a visible funnel. Also, at what wind speed of the cloud-to-ground vortex does a tornado begin? How close must two or more different tornadic circulations become to qualify as a one multiple-vortex tornado, instead of separate tornadoes? There are no firm answers.

How do tornadoes form?

The classic answer -- "warm moist Gulf air meets cold Canadian air and dry air from the Rockies" -- is a gross oversimplification. Many thunderstorms form under those conditions (near warm fronts, cold fronts and drylines respectively), which never even come close to producing tornadoes. Even when the large-scale environment is extremely favorable for tornadic thunderstorms, as in an SPC "High Risk" outlook, not every thunderstorm spawns a tornado. The truth is that we don't fully understand. The most destructive and deadly tornadoes occur from supercells -- which are rotating thunderstorms with a well-defined radar circulation called a mesocyclone. [Supercells can also produce damaging hail, severe non-tornadic winds, unusually frequent lightning, and flash floods.] Tornado formation is believed to be dictated mainly by things which happen on the storm scale, in and around the mesocyclone. Recent theories and results from the VORTEX program suggest that once a mesocyclone is underway, tornado development is related to the temperature differences across the edge of downdraft air wrapping around the mesocyclone (the occlusion downdraft). Mathematical modeling studies of tornado formation also indicate that it can happen without such temperature patterns; and in fact, very little temperature variation was observed near some of the most destructive tornadoes in history on 3 May 1999.

What direction do tornadoes come from? Does the region of the US play a role in path direction?

Tornadoes can appear from any direction. Most move from southwest to northeast, or west to east. Some tornadoes have changed direction amid path, or even backtracked. [A tornado can double back suddenly, for example, when its bottom is hit by outflow winds from a thunderstorm's core.] Some areas of the US tend to have more paths from a specific direction, such as northwest in Minnesota or southeast in coastal south Texas. This is because of an increased frequency of certain tornado-producing weather patterns (say, hurricanes in south Texas, or northwest-flow weather systems in the upper Midwest).

What is a multivortex tornado?

Multivortex (a.k.a. multiple-vortex) tornadoes contain two or more small, intense subvortices orbiting the center of the larger tornado circulation. When a tornado doesn't contain too much dust and debris, they can sometimes be spectacularly visible. These vortices may form and die within a few seconds, sometimes appearing to train through the same part of the tornado one after another. They can happen in all sorts of tornado sizes, from huge "wedge" tornadoes to narrow "rope" tornadoes. Subvortices are the cause of most of the narrow, short, extreme swaths of damage that sometimes arc through tornado tracks. From the air, they can preferentially mow down crops and stack the stubble, leaving cycloidal marks in fields. Multivortex tornadoes are the source of most of the old stories from newspapers and other media before the late 20th century which told of several tornadoes seen together at once.

Are big fat tornadoes the strongest ones?

No, Not necessarily. There is a statistical trend (as documented by NSSL's Harold Brooks) toward wide tornadoes having higher damage ratings. This could be related to greater tornado strength, more opportunity for targets to damage, or some blend of both. However, the size or shape of any particular tornado does not say anything conclusive about its strength. Some small "rope" tornadoes still can cause violent damage of EF4 or EF5; and some very large tornadoes over a quarter-mile wide have produced only weak damage equivalent to EF0 to EF1.

Where Do Tornadoes Come From?

How Fast Can A Tornado Go?

What Are The People Called Who

Study Tornadoes?

How Fast Do Tornadoes Move?

How Long Is A Tornado Usually On

The Ground?

What Direction Do Tornadoes Spin?

Where Do Tornadoes Occour?

Has Every US State Had A Tornado?

Do Tornadoes Really Stay Away From

Gullies, Rivers, and Mountains?

Where Is Tornado Alley?

Where Is The Most Common "Birthplace"

For A Violent Tornado?

Tornado FAQs

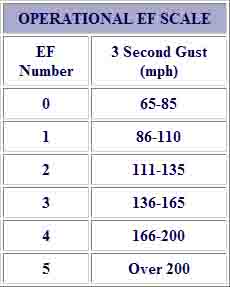

How are tornadoes rated?

They are rated by how much damage and wind speed, using the Enhanced Fujita Scale. An EF-1 is the least damaging and EF-5 is the most damaging. Below is the current EF Scale.

Info courtesy of NOAA

Understanding the threat posed by tornadoes in the United States - particularly the threat of strong and violent tornadoes - is valuable knowledge to everyone, but especially to weather forecasters and emergency management people. Knowledge about long-term patterns helps us be better prepared for natural disasters and could also help scientists detect shifting patterns in severe weather events caused by climate change.